Today’s Spartan Stories post was written by Arlen Hansen, a PhD student in History. Arlen worked in Special Collections and University Archives during Summer 2017, assisting with research related to the University’s 125th anniversary celebration.

William Raymond Taylor may be one of the more colorful characters to have populated the ranks of Woman’s College (later UNCG) faculty. He was certainly one of the most challenging of faculty members for Woman’s College President Julius Foust, and a figure who always “pushed the envelope” of what was possible at the WC.

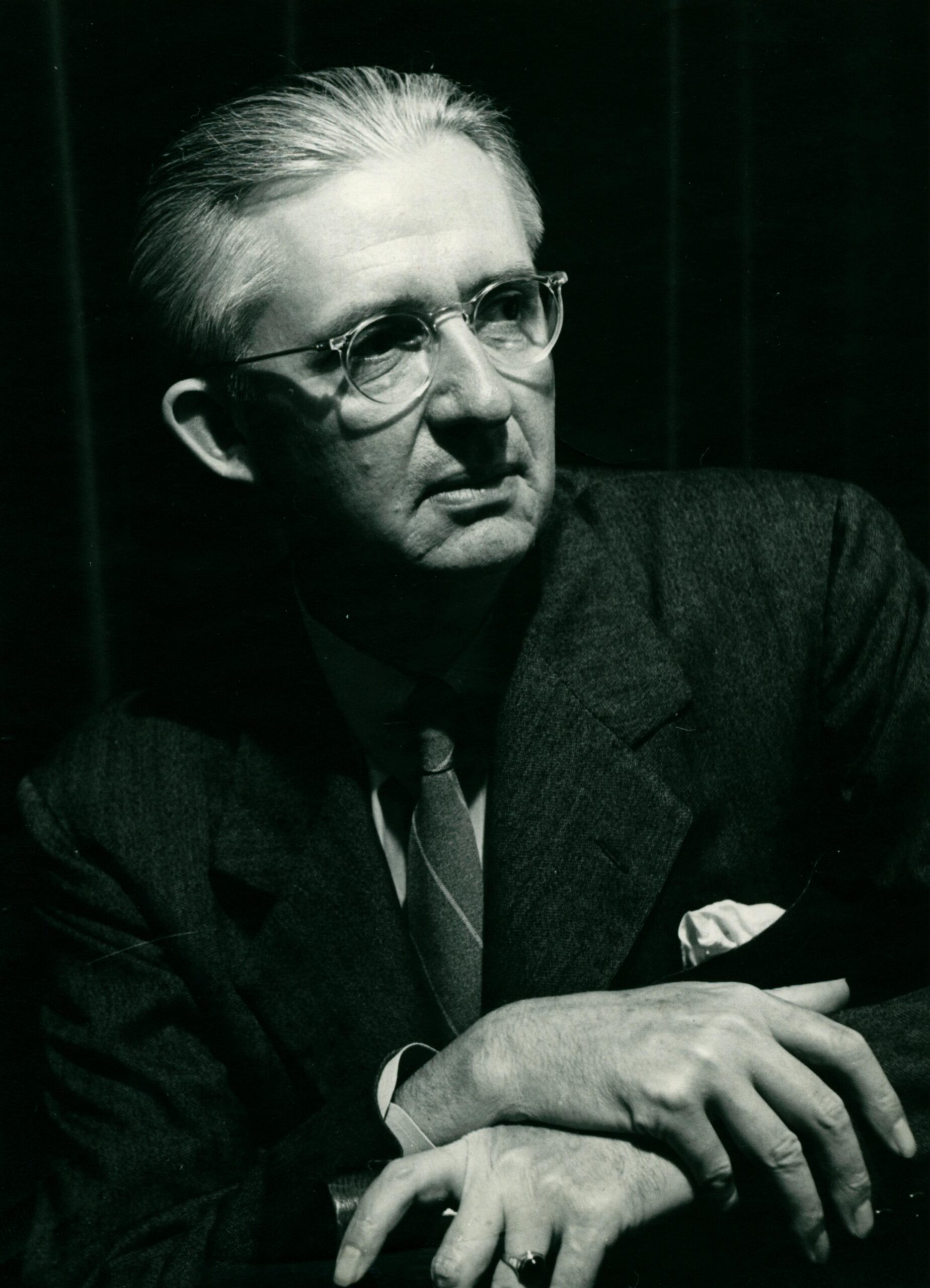

William Raymond Taylor was an English professor at the Woman’s College from 1921 to 1961, but he is better known for being the founder of the University’s Drama and Speech Department. UNCG’s Taylor Theater is named in his honor. A native of North Carolina, Taylor received his B.A. from the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill in 1915, and his M.A. from Harvard in 1916, where he studied with prominent Shakespearean scholars, and became a close friend of the playwright Eugene O’Neill. He taught at Alabama Polytechnic Institute (later Auburn University) from 1916 to 1921, where he founded the drama department there, before coming to the Woman’s College. UNCG historian Allen Trelease writes that knowing Taylor’s love of and involvement in drama, then President of the Woman’s College, Julius Foust was reluctant to hire Taylor and allow him to begin to pursue drama once on site at the Woman’s College.1 It would be the beginning of a long history of tension between Foust and Taylor.

Throughout his 40 years at the Woman’s College, Taylor would divide his time between teaching language and literature, and building the theater program at the Woman’s College. He organized the first drama group at the Woman’s College in 1923, called the Play-Likers. The Play-Likers would evolve into the Drama Department (now the School of Theater and College of Visual and Performing Arts). Taylor would direct more than 200 plays during his years at the Woman’s College. In the early days, Taylor took the Play-Likers on the road, performing plays in small theaters for townspeople in towns throughout the Piedmont and Eastern North Carolina. Also for the first several years of the Play-Likers’ existence, Taylor and his wife, promoted further interest in theater by taking groups of Woman’s College students to New York City to see Broadway plays. On some of these trips they would pack in multiple performances, seeing almost a dozen plays on the trip.2

During this time, Taylor began urging a reluctant Julius Foust to build an auditorium. He, and an associate traveled all over Europe looking at theaters and opera houses for design inspirations for the prospective building. In 1927, when the new Aycock Auditorium made its appearance at the corner of Tate and Spring Garden Streets, Taylor prevailed upon a skeptical Julius Foust to make the building a theater as well. Foust only half-jokingly referred to Taylor’s growing assortment of backstage props, set pieces and paraphernalia as “the devil’s workshop.”3 Taylor would “push the envelope” with some of his 1920s productions, particularly his version of the Broadway hit “Tarnish.” Foust opposed the play’s “low moral tone,” but allowed the production to go forward. Apparently, Foust did not know just how “low” he would consider the moral tone to be. Foust did not go to see the play, but when hearing about its debut, he called Taylor into his office and nearly fired him. Taylor would later say that he never regained Foust’s confidence after “Tarnish.”4

In the late 1940s, Taylor’s position and stature at the Woman’s College began to suffer and diminish. He found himself increasingly incompatible with his associates in the drama division, and critics began to charge Taylor and the Play-Likers with sloppy business practices. The Play-Likers began to disintegrate, audiences declined, and the organization began losing money.5 These problems would eventually lead to drama acquiring status as its own department “in 1953—a development that,” Trelease writes, “involved the removal of W. Raymond Taylor from its leadership.”6 Taylor would return to teaching full-time until his retirement.

After his retirement in 1961, Taylor started a successful stage production and theater supply business with his son. It became one of the largest such firms in the nation. During this time, Taylor and his son designed and installed staging for Las Vegas casinos, and materials for theaters all over the United States, and even in South America. He became an award-winning rosarian (a cultivator of roses). His garden eventually contained over 1200 rose bushes of 250 varieties. In his later years, Taylor also did extensive research in the field of theology, as well as studies in New Testament Greek, after experiencing what he called a “spiritual awakening” at the age of 75. Taylor would tell the Greensboro Daily News in 1972, that around 3:00 AM on the morning of April 3, 1970, he had found himself wide awake and was aware of a voice speaking to him. “I did not hear the voice” he explained, “but in the place of audible sound there was the completely experienced “consciousness of voice.” Taylor said the message of the voice was crystal clear: “You are weak. You are all alone in your loneliness. You need the strength and comfort of my spirit.” A few days later, Taylor, who had never been a church-goer, would tell his wife, a lifelong church-goer, that he wanted to go to church with her on Sunday. Taylor’s “spiritual awakening” would lead to him traveling all over the South, preaching in dozens of Baptist churches, during the last years of his life.7

Taylor died in 1976, at the age of 81.

Article by Erin Lawrimore

1 Allen W. Trelease, Making North Carolina Literate: The University of North Carolina at Greensboro from Normal School to Metropolitan University (Durham: Carolina Academic Press, 2004), 103.

2 Elisabeth Ann Bowles, A Good Beginning: The First Four Decades of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina at Greensboro, 1967), 150, and Trelease, Making North Carolina Literate, 119.

3 Trelease, Making North Carolina Literate, 88.

4 Greensboro News Record, September 23, 1990.

5 Trelease, Making North Carolina Literate, 169.

6 Ibid., 247.

7 Greensboro Daily News, June 18, 1972.