Since the school’s founding in 1892, the library has played a central role in supporting faculty research and student learning. From its humble beginnings in a single classroom to its current massive holdings of physical collections and online journals and databases, the library has sought to keep pace with emerging scholarly trends, changing researcher needs, evolving applications of technology, as well as a growing student population. Starting in 1892 and ending in 1945, this post will examine the profound changes in the library’s collections, services, and space during that time.

When the school opened its doors to students in the fall of 1892, its library consisted of a small collection of donated books. Indeed, President McIver donated a number of reference titles from his private library to help build the school’s collection. Incoming students were encouraged to bring “any books in their possession relating to Science, Literature, History, etc. to be used as reference books.” The State Normal and Industrial School (now UNC Greensboro) had a very small budget for book purchases. The first purchases of books took place at the end of 1892, the school bought standard reference titles and established American and British authors. There were no purchases of more “current” fiction.

Within a short period of time, the library had to be moved to a larger classroom in the Main Building (Foust) to accommodate the growing number of books and periodicals. The new space also had a reception area for visitors. This space was managed by a faculty member and some student workers. In 1895, with the increased use of its library, the school hired its first full time librarian, Annie F. Petty. Ms. Petty was able to introduce a more formal method of cataloging works and meeting user requests. She also oversaw the move of the library’s collections to larger space in the Main Building. She was able to repurpose a former gymnasium to address a number of immediate space issues. By 1900, the library had 3,000 titles. President McIver concluded that this new space was not a permanent solution.

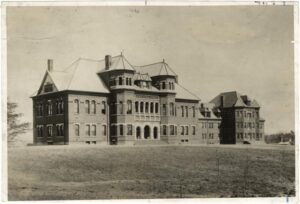

Recognizing that the state legislature would not be making funds available soon for a new library, President McIver decided to write to the philanthropist Andrew Carnegie for help. Mr. Carnegie had established a program to fund the construction of public libraries around the country. McIver’s appeal to support the public education of women seemed to resonate with Carnegie. The State Normal and Industrial School was awarded $15,000 for a new building and nearly $4000 for furniture and shelving. The new library building (Forney) was built on College Ave. It was considered a “modern” building and was equipped with steam heat and electrical lights. Annie Petty described the building as being of “red brick and granite trimmings, and contains seven rooms on the first floor and two on the second. It is furnished in light oak and furnished throughout with Library Bureau furniture, which is artistic, durable, and convenient in every respect.” The Carnegie structure also contained a fire-proof stack-room which had the capacity of 30,000 volumes and also a fireproof vault. Ms. Petty opened the doors of the new library to students in October 1905.

With the ending of World War One and rationing, the state’s legislature turned its attention to reconstruction and a growing postwar economy. The school (now called the North Carolina College for Women) experienced a postwar growth in student enrollment. To meet the needs of this larger student population, the state allocated funds ($75,000) to expand the footprint of the original building. Starting in 1921, a year-long construction project took place. The newly expanded structure was nearly three times as large as the original building. The expanded building would include new public seating to increase the total public seating to 373. The expansion of stack space now allowed for 95,000 volumes. With Ms. Petty’s retirement in 1920, the new space was supervised by Charles B. Shaw. Shaw was a trained librarian. He also was a strong and vocal advocate for libraries. Through his tireless promotion of the library, he would obtain funds to dramatically build the book collection as well as nearly double the size of the library’s staff. The 1920s represented a decade of growth in the library.

On September 15, 1932, the library suffered a significant set-back. A fire broke out in the middle of the night. Thankfully no staff or patrons were injured since the building was closed. Yet, the damage to the building was significant. The greatest damage centered on the reading room and the library science room. The estimates are that 12,000 to 15,000 titles were damaged by smoke and water. But, the majority of the library’s holdings survived in the fire-proof structure in the building. The damage was estimated to be $98,000. The library’s staff and surviving collections were temporarily moved to the Students’ Building.

Under the supervision of the college librarian Charles H. Stone, the rebuilding of the library began almost immediately. The year-long project involved both the repair of fire damaged areas as well as the expansion of the building. The expansion project would involve the addition of two wings to the building and a new stack space. Additionally, the expansion project allowed for a new space for students to enjoy current and “popular” works for recreational reading. Beyond the construction project, the library undertook a collections development project. New titles had to be purchased and other damaged titles replaced. The library would also struggle to “rebuild” its card catalog system since it was almost completely destroyed in the fire. Finally, the library sought to develop new services to support student research. The library instituted the position of a “readers’ advisor” to assist individuals in selecting what “they need or want to read.”

On the eve of the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the school, there was a flurry of news accounts about the library and the college. A number of newspaper articles written in April 1941 noted that the library was recognized as the largest woman’s college library in the South. The school was now called the Woman’s College of the University of North Carolina. The library served nearly 2,300 students and 300 faculty members with approximately 100,000 titles. The library now employed eleven professional staff to meet the needs of 1000 daily users.

Only four years later in 1945, a number of newspaper articles were written discussing the space crunch that the college’s library was deemed to be facing. One article noted that the present structure is “inadequate.” Drawing on the library’s own statistics, these newspaper accounts stressed the steady growth in book purchases and circulation. The authors concluded that these growth numbers were straining the library’s current spaces and services. Additionally, they declared that the library’s seating capacity had not kept pace with the significant growth in the student population.

Not surprisingly, the college submitted a request to the 1945 North Carolina General Assembly for monies to build a new library. Dr. Walter Clinton Jackson, Dean of Administration, stated that $380,000 was requested for the building of the new library. Of the $380,000 asked for the library, Jackson noted that $365,000 would be for construction and $15,000 for equipment. The proposed new three-story library building would be built directly across College Ave. from the 1905 Carnegie library building. The new space would relieve the “cramped” conditions and would include: four large reading rooms, an exhibit room, a rare books room, an audio-visual laboratory, music audition rooms, and a series of small seminar and study rooms. Jackson also noted that the current Carnegie library could be quickly converted into an art center or classrooms. The immediate challenge for the college was to convince the General Assembly of this pressing space need.