Among the many acclaimed alumni who got their start as students in our school’s Department of English is Bertha A. Harris. Born in Fayetteville, NC on December 17, 1936, Harris enrolled in this institution in 1955, when it was known as the Woman’s College (WC). Harris’ writing potential was established early in her time here. During her first year, Harris joined the news staff of the student newspaper, The Carolinian. She was actively involved in other student affairs, serving with the group representing the WC at the International Student Relations Seminar in 1956.

Harris’ wit and dark sense of humor in writing emerged in full display by the beginning of her second year at the school. In a recurrent editorial titled “Calypso,” appearing in the October 8th, 1956 issue of The Carolinian, Harris criticizes the lack of support of the liberal arts on the campus, specifically in relation to liberal arts disciplines not having a building of their own.

“Quite simply, we who major in English and history, art and the languages want and need a place to call home. We are all orphans of the Woman’s College. It is vaguely interesting to hear a French horn during history and stare at a food poster during English… but we’d rather not.”

The specific examples of shared space Harris was protesting against were frequently what would be considered the more gender stereotypical classes at the school, which Harris traced back to the early years of the State Normal and Industrial School for Women. Harris clearly played with the term “Normal” in the school’s earliest name and the more traditional perspective of what would be considered “normal” for women of her time.

“Neither did these normal girls clench their teeth over Chaucer while light-fingered cooks in the next room whipped up a three-layer cake.”

Harris was among the delegates who developed the bill calling for the construction of a new McIver Building and was among the students to attend the State Student Legislature in November of 1956 to promote its creation as the location for liberal arts classes on campus. Ultimately, the McIver Memorial Building was declared unsafe and razed in 1956. It was replaced by the McIver Building in the same location in 1960.

Harris’ rebellion against women being educated to become the stereotypical 1950s woman versus women embracing intellect and culture is evident in later editorials. In a November 6th, 1956 editorial, Harris forcefully criticizes the lack of attendance to a Social Science Forum as well as other intellectual enriching events held at the school.

“You don’t like ‘Modern dance,’ ‘classical’ music, ‘Drama?’ Come now, ladies, I happen to know that relatively few of you have ever been closely acquainted with real dancing, great orchestras, and the greatest concert artists. I happen to know because I am also a product of the North Carolina public schools: and most of you are too.”

Harris ties this lack of enthusiasm for college sponsored academic and art events to the notion that the women are afraid of being perceived as nonconformists and intellectuals.

“I think, ladies, that your’re afraid of being called ‘intellectual,’ ugly word that it is. There’s nothing to worry about, No one will attack you at intermission time by calling you intelligent, or a non conformist, or a little above average… It’s easy to make this college something more than a “factory.” It simply takes a little intelligence, a bit of curiosity, and ‘a little bit of luck.’ Quite soon ladies, if you don’t begin to exercise these faculties, you’re going to have nothing left on this campus but classes– and won’t that be wonderful.”

By the Spring semester of 1958, Harris had instigated so much controversy through her constant critiques of other students, faculty, and the campus in general, that she had a falling out with the editor of The Carolinian.

“I would first like to call a rather startling and distasteful image to your mind. Consider a morning bowl of cereal, perhaps some nasty looking bran flakes that have been drying on the dining hall counter for two days. Suppose you pick it up at seven a.m. At five past seven you add milk… and decide not to eat it. Suppose by accident it is left sitting on the table until lunch time when you find that a glass of water has spilled into it. You see that it is a soggy, nauseous concoction of repulsion, fly specked by the hygienic flies of the Woman’s College dining hall. This, dear editor, is my own personal view of the CAROLINIAN when I open the pages.”

Harris argued that the newspaper had become too much like a tabloid focused on “ill-advised attacks on the personal appearance, habits wearing apparel and intellectual attitudes of this campus.” Some of these apparel-based debates focused on the wearing of black knee-high stockings, the fashion choice of the non-conformists among the students.

The Black Stocking Girls were the intellectuals and free-thinkers among the students and chose to adopt black knee-high stockings as part of their identity. According to 1961 alumna, Laura Goldin Hirsch, in her 2011 oral history, ”They seemed to be wild and crazy… They didn’t fit in.” Naturally, Bertha Harris was one of those Black Stocking Girls. Elizabeth “Betsy” Toth, class of 1963, recalled how she perceived these students in her oral history.

“Yes, it was a beatnik association. And people thought it was just weird, just outstandingly weird, because it reminded people of, like, witches or something… And, of course, everybody thought they were weird. But I think it was kind of–in the back of people’s minds even though they didn’t use the word, I think there was a witch association.”

Laura Golden Hirsch remembered how Harris along with another Black Stocking Girl got in trouble for not standing and singing the National Anthem or the class song. This particular habit of not not conforming to the normal protocols earned Harris a number of enemies in the student body.

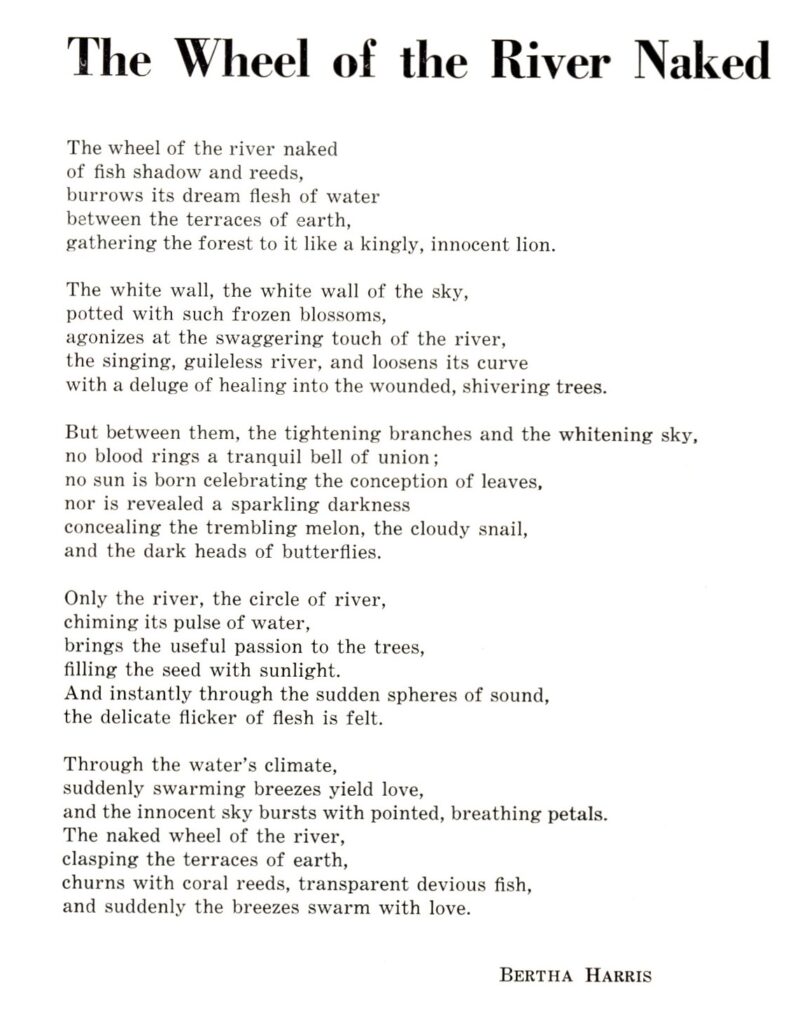

After the falling out with The Carolinian, Harris found another medium to which she could contribute as a writer, joining the staff of the campus literary magazine, the Coraddi, in the Fall semester of 1957. Harris contributed her poetry to the magazine, frequently with one or two poems included in an issue. Much of her poetry uses images in nature or personal visual experiences as the focus. In March 1959, the Coraddi staff organized a panel in which some of their works were to be critiqued. Harris submitted two poems, and her poem, “The Wheel of the River Naked,” was “thought to be the better. It was commented that Bertha had a good ear for poetry lines and her writing held an easy eloquence.”

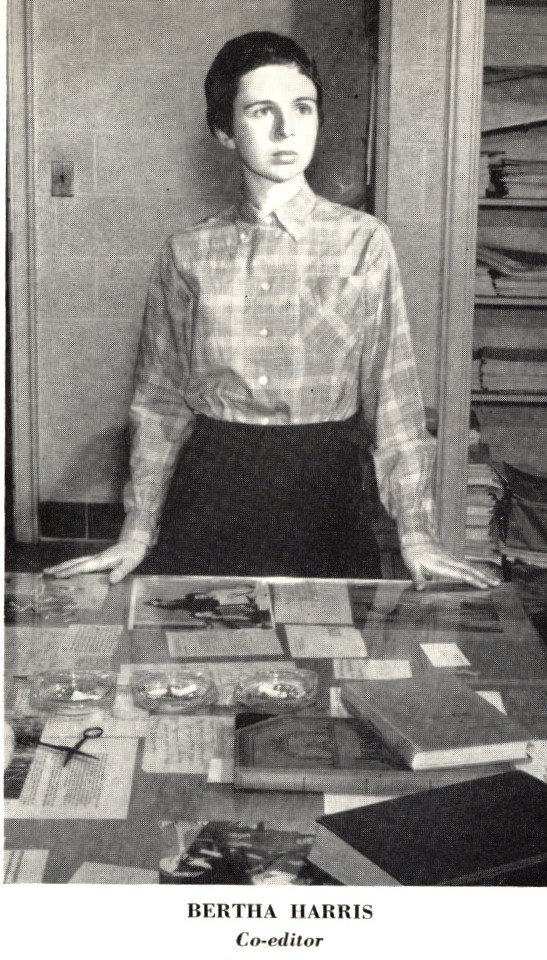

By March of that year, Harris and a friend decided to run as co-editors of the magazine. Harris and her friend were running unopposed for these positions, so they did become co-editors. However, during the Student Government Association assembly announcing the election results, Harris’ contempt for conformity could not be contained, much to the angst of the students in attendance. Once again, when the anthem and class song were sung during the assembly, she did not stand or participate. Outraged, those attending the assembly vocally condemned what was perceived as a lack of patriotism for the campus and the United States and even went on to criticize her black stockings.

In a letter to the editor in the May 14th, 1958 edition of The Carolinian, Harris called for unity, defending her actions as a form of freedom of speech.

“… it is vital in a democracy for the individual student to contribute her opinions… Each must be respected for what they are worth and it must be understood that each individual is responsible to themselves and that which they believe. As we begin our new year together, let us not begin divided.”

This call for unity would not last long. By April of 1959, Harris strongly expressed her contempt for the state of the Student Government Association in a scathing editorial.

“It should be obvious to all with a modicum of perception that a student government, beneath its gloss and high-pressure organizational systems, is in actuality merely a device used by wise administrators to distract and engross the minds and egos of young women having normal glandular activity – and we should hope, a corresponding quantity of imagination…

And, furthermore, that the student government system is encouraged and enforced in order that the young women above mentioned will not turn to diversions so extra-curricular and indeed so imaginative in character that set free, they might undermine a structure depending mainly for its existence on a code of freedom and morality that might better become a Spanish duenna of the old tradition.”

Harris did not need to endure the SGA for much longer, as she graduated at the end of the Spring 1959 as an Honor Roll student and an initiate of Phi Alpha Theta.

The trajectory of Harris’ life continued towards writing, though mostly creative fiction, not poetry. After graduating the WC and spending some time in New York, Harris returned to the school (now UNCG) to earn her MFA in 1969. Harris taught at East Carolina University and UNC Charlotte until 1972. She continued her teaching career as Director of Women’s Studies and a Professor of Performing and Creative Arts at the College of Staten Island CUNY.

Inspired by the momentum of the Women’s Liberation movement, Harris authored the book Catching Saradove (published in 1969). Within a seven year period, Harris published her final two novels, Confessions of Cherubino (1972), and Lover (1976). Lover was her best known novel, inspired by the lesbian movement of the 1970s. Harris published a novella called Traveler of Eternity in 1975, and also wrote two nonfiction books, co-authoring The Joy of Lesbian Sex with Emily L. Sisley in 1977 and authoring a biography about Gertrude Stein for young adults in 1996.

Bertha Harris, after a career as a pioneer in women’s studies and queer fiction, died on May 22, 2005. She is remembered not only through her writings, but also through her name being memorialized as part of the Bertha Harris Women’s Center at CUNY.

By Stacey Krim