February is Black History Month. To celebrate, our Spartan Stories this month focus on remembering important people and events related to the history of African Americans and UNCG. Today’s post is written by guest authors Jordan Rossi and Lisa Withers, students in UNCG’s Graduate Program in Museum Studies. The exhibit of Pieces of the Past will be on display at the High Point Museum until February 18, 2015.

What do you do when you witness or experience injustice? How do you share your reactions to community or government decisions? Do you protest? Create art? When the state of Mississippi voted to keep the Confederate battle cross in their state flag, activist quilter Gwendolyn Magee responded by making a narrative quilt. The product, Southern Heritage/Southern Shame, layered images of the Confederate flag, bodies hanging from nooses, and the hood of a Ku Klux Klan robe. To Magee, keeping the Confederate battle cross on the state flag celebrated a heritage that enslaved, repressed, and murdered African Americans. She channeled her outrage through her art. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, Magee skillfully used fabric to share her reactions to past and present events, to create awareness of racial injustice, and to share stories of the African American experience in the United States.

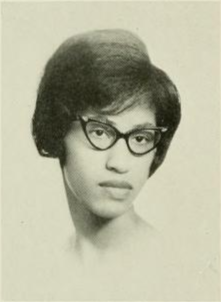

Although Gwendolyn Magee lived in Jackson, Mississippi, for most of her life, she grew to adulthood in the Triad. Raised in High Point, North Carolina, Gwendolyn Magee moved to Greensboro in 1959 and attended Woman’s College. The years spent as a college student in Greensboro, planted the seeds of activism Magee would nurture throughout her life and in her quilts. In the wake of the 1960s sit-ins in Downtown Greensboro, Magee and four black students picketed businesses on Tate Street, which remained segregated. In 1963, student-led protests pushed Tate Street businesses to desegregate.

On campus, Magee also petitioned for inclusion in activities. She and a friend auditioned for a dance routine in their Junior Class Show, but were not selected to participate. Both experienced dancers, the women believed they did not make the cut because they were African American. Magee and her friend volunteered to run the lights during the show. They jumped on stage and danced alongside their white classmates. Experiences such as these led to additional expressions of activism during graduate school, before Magee ultimately turned to quilting as her medium for advocacy.

Magee began quilting in 1989, just before her eldest daughter left for college. Her early work included traditional patterned quilts made for her family (Infinity) and abstract quilts (Hot Ice). Soon, Magee grew dissatisfied with the characterization of African American quilts as folk art. In search for contemporary, African American quilts, Magee found an activist art community, in which many of the artists were African American women quilters.

“But when I began looking at what some other African American quilters were doing, that’s when I became dissatisfied with not doing anything that had cultural relevance but just doing work that essentially was pretty. Well it’s more than pretty but it still didn’t feel as if it mattered all that much in the greater scheme of things, compared to the narrative work which I’m doing today.” -Gwen Magee Oral History Interview

|

| Pieces of the Past: The Art of Gwendolyn Magee exhibit on display at the High Point Museum until February 18, 2015. Image courtesy of Lisa Withers. |

Magee began using her artistic talent to make quilts depicting the African American experience. For example, When Hope Unborn Had Died, is one of several quilts depicting slavery. Magee also made quilts in reaction to modern events. Her quilt, Requiem, is an expression of sorrow for the loss of African American culture when Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans. Until her death in 2011, Magee dedicated her artistic talents to sharing knowledge, sparking community dialogue, and building a better future. Magee’s quilts challenge us to evaluate the state of American society.

Magee remained relatively unknown in North Carolina until the Woman’s College Class of 1963 and the UNCG Art Department exhibited her work on UNCG’s campus. Magee’s work traveled to her childhood home of High Point in Pieces of the Past: The Art of Gwendolyn Magee, an exhibit created in partnership between the High Point Museum, the UNCG Museum Studies program, and the North Carolina Humanities Council. Pieces of the Past will be on display at the High Point Museum until February 18, 2015. More information and pictures of Magee’s quilts can be found at www.gwenmagee.com.