While African American students were banned from enrolling at the school now known as UNC Greensboro prior to 1956, the campus during its earlier years operated primarily on the labor of African American men and women who served as cooks, janitors, handymen, and others who worked behind the scenes.

Little is known about these early African American employees, but the 1913 edition of the student yearbook (known at the time as the Carolinian) carried a short article about them as part of its section celebrating the school’s twentieth anniversary. This section, titled “Some Old Servants of the College,” highlights the contributions of many of the workers “who have served our Alma Mater long, faithfully and honestly.” The language used and viewpoints presented are indicative of how the white female student body viewed the African American service workers.

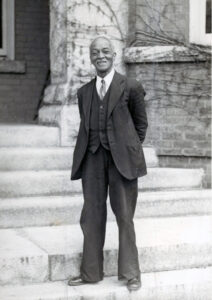

The largest portion of the article is dedicated to Ezekiel “Zeke” Robinson, who the author notes “is now the acknowledged ‘power behind the throne.'” After being hired by president Charles Duncan McIver at the school’s opening in 1892, Robinson managed the school’s large support staff, nearly all of whom were African American. He is praised in the article for his faithfulness to the school, nothing that “no member of the faculty has ever felt more responsible for the College than Zeke has.”

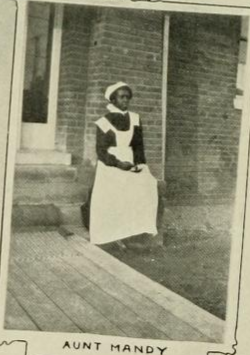

Amanda “Aunt Mandy” Rhodes, who also worked at the school at its opening, is also singled out for praise. Rhodes served as a dormitory housekeeper, and the article notes that “there isn’t a girl who has lived on Aunt Mandy’s hall whose love she hasn’t won by her irrepressible enthusiasm and her interest in the girls and in everything they do.”

William “Uncle William” Peoples is described in the article as “our most talented servant,” as he “can pack, wrap, and dispatch packages, deliver and open boxes, fix electric lights, force the most difficult trunk locks, and a hundred other necessary things.” Peoples, who arrived at the college around 1901, is also praised for his sense of humor.

The article concludes with brief mentions of “a few more of the many servants who have proved indispensible [sic] to the College.” These include “Uncle Henderson, and old cook of the College, and an interesting character, who died in service here” as well as “Johnson, janitor at the Training School for many years, [who] has always won the love and respect of both teachers and children by his integrity, his faithfulness, and his polite and willing service” and his wife Nannie, “maid in Senior Dormitory, and the sworn friend of every Senior.”

Needless to say, the State Normal would not have succeeded without the contributions of these and the many other African American employees who ensured that the lights operated, the buildings and grounds were clean, the students and staff were fed, and the general operations proceeded smoothly and did not disrupt the school’s educational mission.

By Erin Lawrimore