On April 6, 1917, the United Stated officially entered World War I. With the institutional motto of “Service,” the women of the State Normal and Industrial College (now UNCG) sought ways to contribute to the war efforts. Students came together to observe meatless and wheatless days, take classes in food conservation, raise money for the War Relief Fund, and make surgical dressings.

During the summer of 1918, ten Normal women heeded President Woodrow Wilson’s call to increase American food production and reduce food waste by volunteering to work on a 300-acre farm just outside of Greensboro. Most of these Farmerettes had no experience with farm work. In fact, most were not from rural areas at all. But, according to one student – Marjorie Craig (class of 1919) – these women “volunteered for that phase of war work because there was so little else we could do to help win the war … We were told that all the food produced at home made possible a greater supply for the soldiers.”

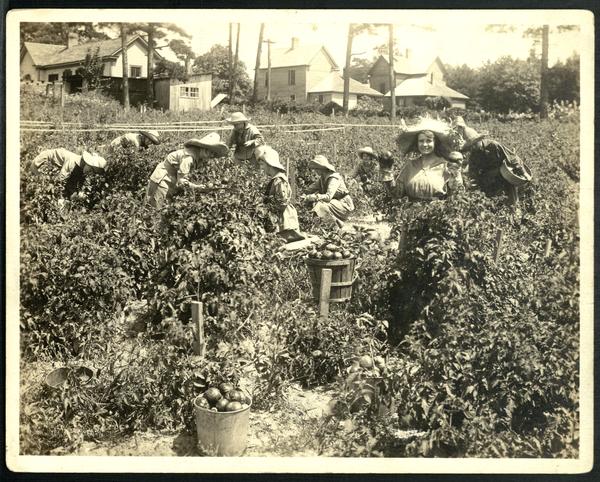

The Farmerettes knew that their presence in the fields might not be welcomed. As Craig noted, “we had been warned beforehand that we would be laughed at and we had prepared to ignore it.” In khaki uniforms and straw hats, these Farmerettes performed all but the heaviest agricultural labor – hoeing corn, pitching hay, threshing wheat, harvesting vegetables, feeding pigs, milking cows, and performing numerous other farm tasks. Work days began at 8 a.m. and continued until 5 p.m., with a one-hour break for lunch.

Campus administrators lent a hand, with J.M. Sink, superintendent of buildings and grounds, supervising their work. Even President Julius Foust stepped in to drive the reaper to cut the wheat.

Ten years after this summer, Margaret Hayes (class of 1919) recounted her time on the farm: “Being a Farmerette I count as one of the most worthwhile experiences of my life. We were engaged in something that we felt was real and vital, not just puttering, as we suspected was the case with some of the war work.”

There were tangible results: hundreds of cans of vegetables, as well as products that could not be canned. In total that summer, these students worked to produce 1100 bushels of wheat, 3000 bushels of corn, 2500 gallons of tomatoes, and 2000 gallons of beans. Most of these foodstuffs were used in the campus pantry the following semester. But perhaps more important than the resulting products, the ten Farmerettes united to fight misconceptions about women’s work abilities and contribute to the war effort in their own unique way.

By Erin Lawrimore